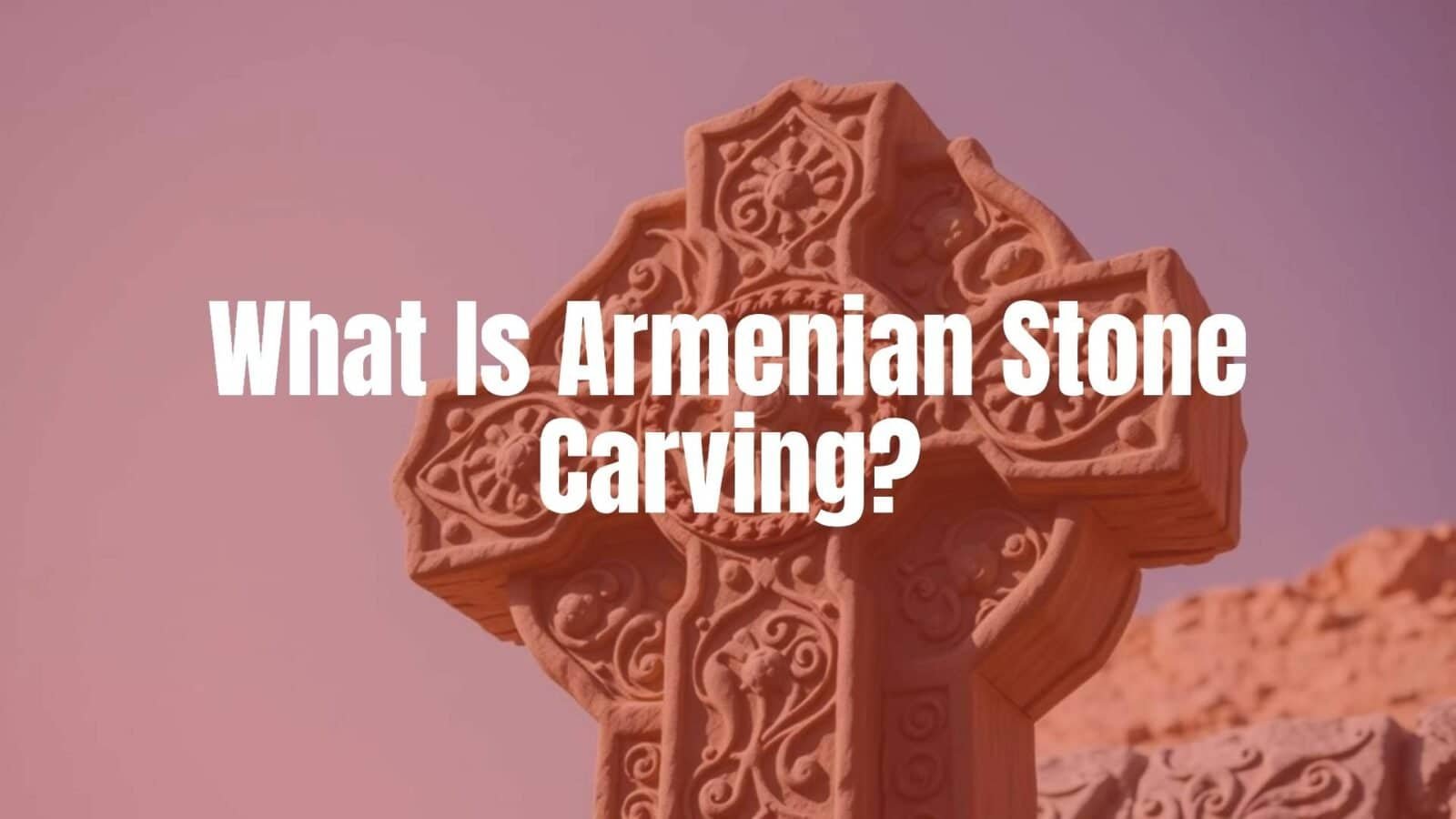

Armenian stone carving is an ancient art closely tied to the country’s culture and faith. These carvings are more than decoration. They are lasting signs of belief, memory, and great skill. They appear as memorials, building details, and historical records. The best-known form is the khachkar, or “cross-stone.” A khachkar is a carved memorial stele with a cross and rich patterns such as rosettes, interlace, and plant designs. This tradition is a hallmark of medieval Christian Armenian art and has UNESCO recognition for its meaning and craft.

Beyond khachkars, Armenian stone carving covers many forms: rich church and monastery ornament, detailed bas-reliefs, medallions, and inscriptions. Artists shape local stone, especially volcanic tuff, into scenes of faith, stories from history, and symbols filled with meaning. Each carving tells a story and shows the steady spirit and skill of the Armenian people through the ages.

How did Armenian stone carving develop through history?

Origins in pre-Christian Armenia

Armenia’s link to stone carving goes back before Christianity. Stone building and carving were already strong in Urartian times and show early mastery. Much pre-Christian sculpture was lost when St. Gregory and the royal court destroyed pagan remains, yet some pieces still point to that deep past.

One important group is the large carved stones called vishap-k’ar (“dragon stones”). These look like tailless whales with fish-like designs, date to the 2nd-1st millennia B.C., and often stand near springs or lakes. Finds from the Artaxiad and Arsacid periods (about 2nd century B.C. to 4th century A.D.) include a bronze head of Aphrodite near Erzinjan and a small marble female torso from Armavir, showing the impact of Hellenistic art. The 1st-century A.D. temple of Garni also shows early carving: lion heads, acanthus friezes, and fine geometric and floral reliefs.

Influence of Christianity and the rise of khachkars

When Armenia adopted Christianity in the early 4th century, stone carving changed course. The cross, used since this time, became the main symbol in art. Early cross-stones were simple. “Winged cross-stones” appeared in the 7th century, though few survive. After the 8th century, cross-stones with rectangular bases became common.

The khachkar truly grew in the 9th century, after Armenia regained strength following Arab rule. The oldest dated khachkar (879) stands in Garni and honors Queen Katranide I, wife of King Ashot I. By then, the idea of the Armenian cross-stone had taken shape, with rich geometric and plant motifs that set a path for later growth.

Medieval innovations and the golden age of stone carving

From the 12th to the 14th century, khachkar carving reached its peak. Designs became more complex, and methods grew more advanced. Many khachkars looked like lace in stone, carved on several levels, and could be very large. Some stood on altar-like bases and included figures.

Masters pushed their craft to new heights, joining fine detail with rich meaning. The “Amenap’rkich’” or “Savior of All” type replaced the plain cross with a full Crucifixion scene. The earliest known example (1273) is at Haghbat. Momik, a multi-skilled artist of the late 13th century (also an architect and miniaturist), is a leading name of this time. His khachkar from Noravank (1308) shows the art at its finest.

Periods of decline, revival, and preservation

Khachkar carving fell sharply after the Mongol invasion at the end of the 14th century. A revival came in the 16th-17th centuries, though the peak of the 14th century was not reached again. Regional styles appeared, such as the Julfa school, known for accurate, regular crosses.

The craft still continues today. Yet many khachkars have been lost to war, weather, and deliberate destruction, such as the wiping out of the Julfa cemetery between 1998 and 2005. Since 2010, “Armenian cross-stone art, symbolism and craftsmanship of khachkars” has been on UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. This calls for ongoing care and recording to protect this part of Armenian identity.

| Period | Main features | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Christian | Urartian stone work; vishap stones; Hellenistic influence | Garni temple reliefs; Aphrodite head; Armavir torso |

| Early Christian (4th-8th c.) | Cross becomes central; early cross-stones; winged crosses | Scattered early cross-stones |

| 9th-11th c. | Khachkar concept formed; richer motifs | 879 Garni khachkar (Queen Katranide I) |

| 12th-14th c. | Golden age; multi-level carving; figure scenes | 1273 Haghbat; Momik’s 1308 Noravank |

| 16th-17th c. and later | Revival; regional schools; modern practice | Julfa style; ongoing workshops |

What are the types and styles of Armenian stone carvings?

Khachkars (cross-stones)

Khachkars are the best-known form of Armenian stone carving. The name means “cross-stone” (from Armenian խաչ xačʿ “cross” + քար kʿar “stone”). A central cross stands above a rosette or solar disc. The cross is rarely plain. It is framed with leaves, grapes, pomegranates, and bands of interlace. No two are the same, as makers adjusted the design for each purpose.

Motifs around the cross also carry strong meaning. Rosettes, interlace, and plant forms fill the surface, forming a dense, striking pattern. Some have a cornice with saints or Bible scenes. Khachkars were raised for many reasons: for the souls of the living and the dead, to mark victories, to celebrate new churches, or as protection from disaster. About 40,000 survive, showing how important they are in Armenian life.

Tombstones and memorials

Many Armenian gravestones are khachkars, especially in old cemeteries like Noraduz, but there are other forms too. These stones are personal and communal signs of memory and faith. Inscriptions often give dates, names, and sometimes the artist, linking us to the past.

Regional and period styles appear. Julfa’s cemetery had long khachkars without pedestals and special figure scenes on the cornice and lower parts. Another common memorial type, popular in 16th-century Julfa and seen in Iran and Azerbaijan, is the ram figure carved in the round. These forms show the many ways Armenians honored their dead in stone.

Architectural ornamentation

Armenian stone carving also shines in building decoration, turning churches and monasteries into art. From the earliest churches onward, façades show relief sculpture. Sixth-seventh century churches often have carved bands.

Richer reliefs appear around windows and door tympana at sites like Ptghni, Mren, Zvart’nots’, and Odzun. The capitals at Zvart’nots’ (7th century) are very detailed, some like woven baskets with monograms. The four main pillars carry huge heraldic eagles. The 10th-century Church of the Holy Cross on Aght’amar island is covered with reliefs: Old Testament scenes, a lively vine scroll, and large figures of the four Evangelists. These carvings are part of the building’s message, sharing belief and history in stone.

Bas-reliefs, medallions, and inscriptions

Bas-reliefs, where figures stand slightly above the background, appear in many places. At Aght’amar, deep carving and large figures blend Eastern and Armenian styles, with front-facing Bible figures. Medallions with tightly woven geometry appear on many khachkars and can suggest the world under the cross or the mystery of Christ.

Inscriptions play a key role, giving dates, dedications, and names of patrons or artists. Khachkars often carry this data, which helps us learn about the time and people behind the works. A modern example is the “Traveler’s Pathway” at the Stone Art Guesthouse in Pemzashen by master carver Volodya, with calligraphic texts and coats of arms carved into multi-colored tuff.

What techniques and materials are used in Armenian stone carving?

Traditional hand tools and carving processes

Making Armenian stone carvings, especially khachkars, calls for steady hands and long practice. The basic approach has stayed the same for centuries. Carvers choose a stone and plan the layout, often drawing directly on the surface. With chisels of different sizes, hammers, and other hand tools, they patiently cut the design.

Designs are carved on several levels to add depth. On a khachkar, the cross often stands at the highest level, sometimes nearly an inch deep. The finer lacework and patterns sit at lower levels. This gives strong play of light and shadow and brings out the design. Thin tendrils and tight interlace need sharp control and long training, usually passed down from master to student.

Types of stone preferred by Armenian artisans

Armenian carvers mainly use local stone. The favorite material for khachkars is tuff, a volcanic stone with many colors. It is easier to work than many rocks and shapes much of Armenia’s look, including Yerevan’s pink façades. The area around Pemzashen has tuff, pumice, and other stones, making it a natural center for stone art.

Other stones appear too. A 12th-century “Khachkar (Stone Cross)” at The Met is basalt, a harder volcanic rock. Carvers choose based on what is nearby, how the stone cuts, and the look they want. The colors-especially when wet-often guide the design so the stone’s natural beauty adds to the carving. Working many kinds of stone shows the skill of Armenian carvers.

| Tool / Material | Use / Feature |

|---|---|

| Point and flat chisels | Roughing out, shaping, and fine detail |

| Hammers and mallets | Driving chisels with controlled force |

| Compasses, rulers, templates | Laying out geometry and repeating patterns |

| Tuff | Workable, colorful volcanic stone; common for khachkars |

| Basalt | Dense, durable volcanic rock; finer edges, slower to cut |

Symbolism in motifs and patterns

Symbolism sits at the center of Armenian stone art. The cross stands for salvation through the Crucifixion and the Resurrection. On khachkars, the cross often “flowers,” with leaves rising from its base. This points to new life and links the cross to the Tree of Life.

Other symbols add layers of meaning. Rosettes or solar discs under the cross can suggest the sun or eternity. Interlace and plant motifs are common. Grapes stand for Christ and the Eucharist. Pomegranates point to fertility, abundance, and the blood of martyrs. The infinity sign at the bottom of many khachkars, paired with the cross, speaks of the flow of life and national beliefs. Even the five key points on a cross-stone-the four wing tips and their center-carry meanings about grace, forgiveness, and the kingdom of heaven.

What are khachkars and their importance in Armenian stone art?

What do khachkars represent?

Khachkars, or Armenian cross-stones, are more than decoration. They are carved signs of Armenian faith, history, and identity. The name joins “cross” (xačʿ) and “stone” (kʿar), which sums up their core idea. They show the Christian cross in a distinct Armenian way that stresses life, rising from the dead, and eternity. Medieval texts call the cross “the life-giving sign,” and the design starts and ends with it.

Khachkars were raised for many aims: prayers for the living and the dead; to record victories or new churches and bridges; and as shields against harm. Each one is a quiet prayer, a record of an event, and a marker of the care of a person or a community. They stand at the center of Armenian spiritual and cultural life.

Design elements of khachkars

Though each khachkar is different, they share key parts. The main feature is the cross, usually above a rosette or a solar disc. The cross is often decorated and looks “living” or “flowering.” Leaves may grow from its base, pointing to the Tree of Life and hope in the Resurrection.

The rest of the stone is carefully filled with pattern. Interlace and tight geometry, often called lace-like, stress connection and the reach of the cross. Grapes and pomegranates appear often, linking to Christ, the Eucharist, and plenty. Some tops show a cornice with saints or Bible scenes, or a Deesis with Christ Pantocrator. Many bases carry an infinity sign, adding to ideas of eternal life and shared beliefs. Together these parts form a deep, visual meditation on faith.

Notable khachkars and examples across Armenia

Armenia holds countless fine khachkars. A standout is the 1213 khachkar at Geghard, likely by masters Timot and Mkhitar. The Holy Redeemer khachkar at Haghpat (1273) by master Vahram is another high point. Goshavank has a famous khachkar carved in 1291 by master Poghos.

UNESCO recognition and endangered status

In 2010, “Armenian cross-stone art, symbolism and craftsmanship of khachkars” joined UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This shows their deep artistic, spiritual, and historical value for Armenia and beyond.

Yet many khachkars are at risk. Weather, war, and neglect have destroyed large numbers. A grave case is the planned destruction of the Julfa cemetery in Nakhichevan between 1998 and 2005, where thousands of khachkars were wiped out. Even inside Armenia, some stones face harm, neglect, or moves for new burials or decoration, which can strip them of their original setting. Protection work and careful care are needed so future generations can learn from these stones.

Where can you see Armenian stone carvings today?

Major monuments and monasteries

To see Armenian stone carving at its best, visit the country’s major monuments and monasteries. These places show many centuries of craft. Geghard, Haghpat, Sanahin, Goshavank, Tatev, and Noravank hold rich groups of khachkars and reliefs. Geghard, cut partly into the mountain, includes a fine 1213 khachkar inside its rock-hewn spaces.

Haghpat and Sanahin (both UNESCO sites) hold many khachkars, including Haghpat’s 1273 Holy Redeemer stone. Noravank has striking reliefs, like the Birth of Adam with God and the Crucifixion on the west tympanum. These sites show how carving fits the whole design and spirit of the complexes, with details on walls, columns, and doorways.

- Geghard: rock-cut spaces, 1213 khachkar

- Haghpat: Holy Redeemer (1273), many stones

- Sanahin: rich medieval reliefs and khachkars

- Noravank: fine tympana and Momik’s work

- Goshavank and Tatev: varied styles and periods

Cemeteries and open-air museums

Ancient cemeteries are open-air galleries of this art. Noraduz on Lake Sevan’s west shore has the largest group in Armenia, with about 900 stones from many times and styles. Walking there shows the growth of the art-from early simple forms to rich medieval work-each stone a quiet story.

Julfa’s cemetery in Nakhichevan was destroyed, but copies help keep its memory alive. You can see many replicas in churchyards and parks in Armenia, including about 20 in Gyumri. These places, whether ancient yards or recent memorial spaces, offer a strong, moving way to meet Armenian stone art.

International collections and diaspora sites

Armenian stone art also appears worldwide. Museums hold khachkars, making them known to many people. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York shows a 12th-century Armenian “Khachkar (Stone Cross)” from Lori-Berd, carved in basalt with an interlace frame and a large cross resting on the heads of the four evangelists.

In the 20th century, new khachkars spread as symbols of culture and strength. Many stand in public places as memorials to the victims of the Armenian Genocide. Examples appear at the Vatican Museums; Canterbury Cathedral’s memorial garden; St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney; the Colorado State Capitol; and the Temple of Peace in Cardiff. France has nearly 30 in public spaces, and Poland has about 20, linked to its historic Armenian community. These sites show the reach and lasting meaning of Armenian stone carving.

Who are the notable Armenian stone carvers and workshops?

Master carvers throughout history

Many master carvers shaped this art, though we know the names of only some. Momik, a leading late 13th-century artist, is famous for khachkars and for work as an architect and miniaturist. His 1308 Noravank khachkar (kept at Etchmiadzin) shows great skill and detail.

Other known names include masters Timot and Mkhitar, linked to the 1213 Geghard khachkar, and master Vahram, who carved Haghpat’s Holy Redeemer (1273). Master Poghos made the 1291 khachkar at Goshavank. Their work lifted stone carving to a high, spiritual art.

Contemporary artisans and their ateliers

The craft is alive today. In Yerevan and other regions, carvers still make khachkars for memorials, churches, and private orders, teaching new students along the way.

In Pemzashen, master carver Volodya Saribekyan and economist Hovhannes Margaryan turned their gardens into an open-air gallery and workshop. Volodya teaches visitors to carve tuff and design their own pieces, from Mount Ararat scenes to mosaics. His works also stand in the village park. This effort keeps old methods in use and shares Armenian values and local identity through stone. Another modern master, Ruben Nalbandyan, made a replica of Momik’s Noravank khachkar now shown at the Museum of the Bible, proving the strength of today’s craft.

What threats and preservation efforts exist for Armenian stone carving?

Endangered khachkars: destruction and loss

Many Armenian stone carvings, especially khachkars, face danger. Weather, war, and planned destruction have taken a heavy toll. A major loss was the clearing of the Julfa cemetery in Nakhichevan between 1998 and 2005. In 1648 it held about 10,000 khachkars; by 1998 about 2,700 remained, and then all were destroyed. This happened despite a 2000 UNESCO order for protection.

Beyond that, stones in areas once part of historic Armenia-now in Turkey, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Iran-are often not recorded or protected and can be lost or removed. Inside Armenia, some stones are damaged, ignored, or moved for new burials or decoration, breaking their original setting. Over a thousand years, some 50,000 khachkars were made. Many are now unstable, and the rest still face risk.

Conservation projects and safeguarding initiatives

Many people are working to protect these works. UNESCO’s 2010 listing raised global awareness and gave support for protection.

- Recording and study: careful cataloging and photo surveys

- Repair: stabilizing and restoring damaged stones

- Education: teaching the next generation and public outreach

- Craft support: active workshops that pass on skills and make new works

Workshops like those in Pemzashen help keep methods alive by teaching and creating. These steps help protect old stones and keep the carving tradition going.

How to experience Armenian stone carving as a visitor

Visiting ancient carving sites and museums

If you want to explore Armenian stone carving up close, visit the places where the stones still stand. Plan stops at Geghard, Haghpat, Sanahin, Goshavank, Tatev, and Noravank. These sites are spiritual centers and open-air galleries with many khachkars and reliefs, often set in dramatic landscapes.

Also visit Noraduz cemetery, the largest collection of khachkars in Armenia. Walking among hundreds of stones gives a strong sense of history and faith. For indoor collections, go to the Historical Museum in Yerevan and the museum complex at Echmiadzin. Abroad, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York shows a 12th-century Armenian khachkar.

Workshops and learning opportunities with local artisans

If you want a hands-on choice, join a workshop with a local carver. In villages like Pemzashen, masters such as Volodya Saribekyan teach visitors how to work tuff and design simple pieces. You can make a small carving and bring home your own piece of Armenia.

Workshops help you see how design, tools, and meaning come together. They connect you with a living craft and show how old skills still grow in new times.

Cultural festivals and related events

You can also look for festivals and events that highlight traditional arts. While few events focus only on stone carving, many larger cultural programs in Armenia include craft demos, music, dance, and history, with carvers showing their methods.

Special shows-like “Breath of God: Armenia and the Bible” at the Museum of the Bible (opened March 2023)-offer well-planned displays on how stone art, faith, and history meet. These events help place Armenian stone carving in daily life today and show why it still matters.

Leave a comment