What Is Armenian Khachkar Art?

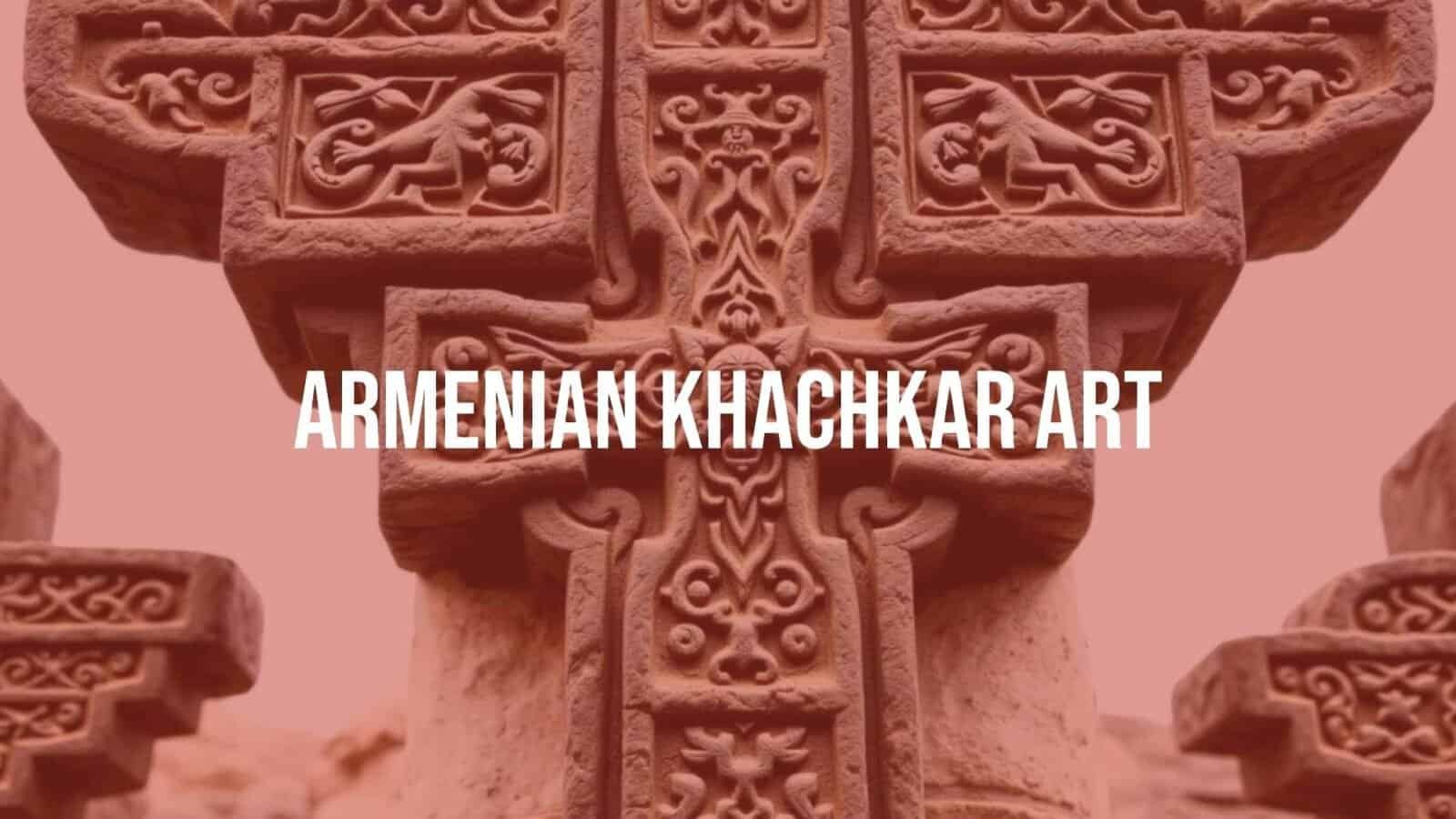

Armenian khachkar art, pronounced “chotch-car,” is a clear and deep expression of Armenian culture and Christian faith. A khachkar (or khatchkar) is a carved memorial stele, literally “cross-stone” in Armenian (խաչ xačʿ “cross” and քար kʿar “stone”). These stone crosses are much more than decoration; they are sacred objects used to honor the dead, mark events like victories or church building, and even serve as prayers for protection from natural disasters. Since 2010, khachkars, their rich symbolism, and the skilled work behind them have been listed by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Armenians adopted Christianity as a state religion in the early fourth century, and khachkars grew as a distinct Christian tradition that has lasted for centuries. Found across Armenia and its historic lands, khachkars stand for national identity, faith, and endurance. While most share a rectangular shape, every khachkar is unique, showing the personal style and devotion of its maker.

Definition and Meaning of Khachkar

At its core, a khachkar is an Armenian cross-stone, a tall stele carefully carved with a cross as its main feature. The Armenian word, խաչքար (pronounced [χɑtʃʰˈkʰɑɾ]), directly means “cross-stone.” They are more than gravestones, even though many stand in cemeteries. Khachkars serve wider goals: prayers for the souls of the living and the dead, and markers of important moments in community life.

Each khachkar carries layers of meaning. Medieval Armenian texts call them “life-giving signs.” Their detailed designs invite thought about Christ and the ties between all things. The cross, always central, links the human and the divine, and points to hope in daily life and in eternal life.

Key Characteristics of Khachkar Art

The central cross is the most striking feature, often placed above a rosette or solar disc. The cross is rarely plain. It usually comes with interlace patterns, leaf and vine forms, and sometimes figures. Deep, fine carving creates a lace-like look, like embroidery in stone.

The rest of the stone often carries rich decoration: leaves, grape clusters, pomegranates, and interlacing bands fill the surface with meaning. A cornice may crown the stone, at times with scenes from the Bible or images of saints, adding story and spiritual message. The fine detail and layered carving make each khachkar a one-of-a-kind work that shows the maker’s skill and vision.

Symbolism and Spiritual Significance

Khachkar symbols come from Armenian Christian belief and cultural identity. The cross stands for Christ’s sacrifice and rising from the dead, and so for salvation and life without end. Grape vines and pomegranates suggest fruitfulness, abundance, and the tree of life, joining Christian ideas with older Armenian symbols.

Endless-looking geometric lines and interlaces are not just for beauty; they point to eternity and God’s boundless nature. The cross at the center, held by these patterns, shows the always-present power of Christ. Many khachkars serve as visual prayers about God and the mystery of Christ. They keep faith, heritage, and the spirit of the Armenian people in view.

History and Development of Khachkar Art

The story of Armenian khachkars spans centuries of faith, art, and cultural strength. Khachkars took shape in medieval Armenia, growing from earlier Christian signs and architectural details. Their rise reflects the role of the Armenian Church and the country’s unique history.

From simple beginnings, khachkars grew more complex in design and deeper in meaning. The tradition saw high points and low points, often matching Armenia’s political and social changes. Still, it endured, showing how deeply rooted it is in Armenian life.

Origins in Medieval Armenia

The first true khachkars appeared in the 9th century, as Armenia revived after Arab rule. Earlier, rougher cross-stones exist, but the form we recognize today took shape then. The oldest dated khachkar (879) was set up in Garni for Queen Katranide I, wife of King Ashot I Bagratuni. It marks a key step in khachkar art, showing both form and purpose.

The roots go back further: “winged” crosses and cross designs appeared in the 4th century, when Armenia adopted Christianity. By the 6th-7th centuries, the main conditions were set for the full growth of khachkars, paving the way for the rich cross-stones of medieval Armenia.

Evolution of Styles and Motifs

Khachkar styles and motifs changed over time. By the 11th century, structure, style, and tools were largely set, with fine examples at sites like Khtskonk in Western Armenia. The 12th-13th centuries formed a “golden age,” when the art reached its peak.

In these centuries, makers set khachkars free-standing, into chapels, and on walls. Carvers added larger cornices, sculpted figures, and more complex borders. Red paint appeared, lifting these stones to the level of national masterpieces. Carving became lighter and finer, like lace. Regional schools formed, each with a local style-Ani, Lori-Tashir, and Nakhichevan among them.

Influence of Religion and Culture

Faith and culture shaped khachkars at every step. As the first state to adopt Christianity, Armenia expressed belief through art in strong ways. Khachkars stood as bold signs of Christian identity, in a land often caught between rival powers and religions.

Khachkars also carried Armenian cultural values. Their patterns and motifs drew on native art and blended with Christian symbols. They became a visual language for memory, history, and hope-for good life now and salvation forever.

Periods of Flourishing and Decline

Carving reached a high point from the 12th to 14th centuries. The Mongol invasion at the end of the 14th century broke this growth and led to decline. War and loss slowed work and disrupted traditions.

A revival came in the 16th-17th centuries, showing how important khachkars remained for Armenians. While output rose again, many think the heights of the 14th century were not matched. Still, the tradition continued into the 18th century and saw a strong rebirth in the 20th century as a symbol of Armenian culture.

Main Features and Elements of Khachkars

Khachkars are easy to recognize: a clear layout and rich carving. While each stone is unique, shared features tie them together across time. These parts carry deep spiritual and cultural meaning.

Artisans followed guiding “rules” that kept the message clear while leaving room for creativity. This steady base plus freedom is a big reason khachkars remain so striking.

The Cross as Central Element

The cross is the main feature on every khachkar. It stands out, often carved deeper than the rest so it catches the eye. It usually sits above a rosette or solar disc, linking Christian belief with older Armenian cosmic ideas.

The cross itself is rarely simple. Often Latin in form, it may have ends that seem to flow without corners, hinting at infinity. Around it, leafy tendrils may appear, showing life flowing from the cross-an emphasis on life and renewal. On Amenaprkich-type khachkars from the 13th century, the cross shows the crucified Christ, sometimes with Bible scenes, adding a clear story to the symbol.

Ornamental Patterns and Decorations

The areas around the cross are filled with detailed designs: interlaces, geometric patterns, and plants like leaves, grapes, and pomegranates. These careful carvings can create depth and movement across the stone. Endless geometric lines suggest the unity of all things and the central power of the cross.

Many stones look like several layers of lace, a quality that grew stronger as the art developed. This fine work takes great skill and patience. National symbols-pomegranates, grapes-appear often, tying the stone to Armenian heritage. The result is beauty and depth where every part adds to the larger message.

Iconography and Inscription Panels

Beyond the cross and patterns, many khachkars include images and texts that add meaning. A cornice may top the stone, sometimes with saints or biblical scenes. Rare pieces, like the Noravank khachkar, include a Deesis at the top with Christ Pantocrator and figures like John the Baptist.

Inscriptions became part of the design. They record the stone’s purpose-prayer for a soul, a victory, a church building-and often name the patron and sometimes the master carver, such as Master Poghos on “The Needlecarved” khachkar in Goshavank. These texts link the stone to real people and events and strengthen its memorial role.

Types of Armenian Khachkars

Armenian khachkars are surprisingly diverse despite shared basics. Over time, different types formed, serving special purposes and reflecting local needs and styles. This range shows how flexible and important the art has been in Armenian life.

You will see classic designs, memorial stones, church and monastic pieces, and regional variants. Each adds another layer to the tradition.

| Type | Main Purpose | Typical Features | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classic | Faith symbol, public display | Central cross over rosette/solar disc, rich interlace | Noravank Khachkar (replica at Museum of the Bible) |

| Commemorative/Memorial | Prayer for souls, mark events | Inscriptions naming purpose, patrons | Genocide memorial khachkars worldwide |

| Church/Monastic | Record gifts, mark events | Built into walls or free-standing in complexes | Haghpat, Sanahin, Geghard, Goshavank |

| Funerary | Grave markers with rich art | Classic layout in cemeteries | Noraduz cemetery |

| Amenaprkich | Icon of Holy Saviour | Crucified Christ on the cross, biblical scenes | Sevanavank monastery |

Classic Khachkars

“Classic khachkar” refers to the common, long-lasting form: a central cross above a rosette or solar disc, wrapped in fine interlace and plant patterns. Sizes range roughly 1-3 meters high, 0.5-1.5 meters wide, and 10-30 centimeters thick, with variation.

These stand across Armenia-free-standing, in cemeteries, or set into church walls. They follow the traditional layout with the cross as the focus and wide, delicate ornament around it. The Noravank Khachkar, known through a replica at the Museum of the Bible, shows the deep carving and rich meaning of this type.

Commemorative and Memorial Khachkars

Many khachkars serve memory and prayer. Early stones were raised for the salvation of a soul, living or dead. Others marked victories, church or bridge building, or asked for protection from nature. They are stones of memory and intercession.

Today the tradition continues, especially for remembering the victims of the Armenian Genocide. Hundreds of modern khachkars stand around the globe-from the Vatican Museums to Canterbury Cathedral’s memorial garden and the Colorado State Capitol-showing the power of the khachkar as a sign of remembrance and identity.

Church, Monastic, and Funerary Khachkars

Khachkars are deeply tied to Armenian church life and burial customs. Many stand near churches and monasteries, built into walls or standing inside the grounds. They often record donations or mark key events in religious communities. Haghpat, Sanahin, Geghard, and Goshavank hold major groups of khachkars.

Funerary khachkars stand in cemeteries. While Armenian grave markers vary, khachkars form a special and highly artistic group. Noraduz cemetery, with about 900 khachkars from different periods, is the largest surviving collection and tells much about Armenian life and belief.

Unique Regional Styles

Over centuries, regional schools formed across historic Armenia, each with its own look. Local carving habits, types of stone, and patron tastes shaped these styles. Schools include Ani, Lori-Tashir, Artsakh, Javakhk, Vayots Dzor, Gegharkunik, and Nakhichevan.

The “Amenaprkich” (Holy Saviour) type appeared in the 13th century. These stones move beyond plant motifs to show the crucified Christ on the cross, sometimes with scenes of the Descent or the Resurrection. Only a few survive, mostly late 13th century, including one at Sevanavank. This type marks a clear shift toward figure scenes within the cross design.

Techniques and Craftsmanship in Khachkar Carving

Making a khachkar calls for high skill, patience, and artistic vision. The craft has passed down through generations. It holds old methods while leaving room for personal style. Knowing the steps and materials helps us value the work that turns raw stone into detailed sacred art.

From choosing the block to the final small cuts, each step is careful and purposeful. The work is technical and reflective, as the carver gives the stone both shape and meaning.

Materials Used for Khachkars

Khachkars are mostly carved from local stone, mainly tuff (tuf kar). Tuff is a soft, porous volcanic rock common in Armenia and well-suited for fine detail. Its ease of carving allows the lace-like effects that define the art. Basalt also appears, as in the 12th-century “Khachkar (Stone Cross)” from Lori-Berd (now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

The stone affects texture, color, and feel. Tuff can be pink, orange, or gray, adding visual richness. Mountain stones are durable, which has helped many khachkars survive wars and disasters, standing as witnesses to history.

Traditional Carving Methods

Traditional carving takes time and care. The maker first sketches the design on the stone. This stage can be long, with changes and adjustments until the layout feels right. As master carver Hambik Hambardzumyan notes, this flexible approach means the design can change a lot before cutting begins.

With the plan set, carving starts with hand tools such as die, chisel, and sharp pens. The carver works in layers: outline first, then deeper cuts to build lacework and three-dimensional forms. Keeping straight walls in the cuts is key for crisp lines. Depth can be large; the cross on the Noravank khachkar reaches nearly an inch deep. This layered work creates flowing forms in stone. A single khachkar can take months, and large ones up to a year. Rushing would harm both quality and character.

Famous Khachkar Artisans and Masters

Many khachkars are anonymous, but some masters are known by name. They were artists whose skill raised the craft to high art. Momik, a master in many arts, carved the original Noravank Khachkar in 1308, known for tight detail and rich meaning.

Master Vahram carved the Holy Redeemer khachkar in Haghpat in 1273, often listed among the finest. Master Poghos made “The Needlecarved” khachkar in Goshavank in 1291, loved for its interlocking lace shapes. Masters Timot and Mkhitar likely carved a key khachkar at Geghard in 1213. In recent times, Ruben Nalbandyan has created faithful replicas of historic stones, keeping the tradition alive with high skill. These names, old and new, show the strength and continuity of the craft.

Notable Examples and Places to See Khachkar Art

To feel the scale and detail of khachkars, see them where they stand: old cemeteries, monasteries, and museums at home and abroad. Each site tells a story of faith, history, and art, and connects visitors to Armenia’s cultural life and master carvers.

Whether in original settings or gallery spaces, these stones reveal how the art grew and why it matters. They are living symbols of Armenian endurance and devotion.

Famous Khachkars in Armenia

Armenia is like an open-air museum with about 50,000 cross-stones across the land. Noraduz cemetery, on Lake Sevan’s western shore, holds around 900 khachkars from many periods and styles-the largest surviving group anywhere. The oldest there date to the late 10th century, and some show scenes from village life or weddings.

Other key places include Haghpat and Sanahin monasteries (both UNESCO World Heritage Sites), each with many important khachkars. Haghpat holds the “All Savior” cross-stone (1273) with the Crucifixion. Goshavank has “The Needlecarved” khachkar by Master Poghos (1291). Near Geghard, fine examples stand, including one carved in 1213, likely by Timot and Mkhitar. Sevanavank holds a rare Amenaprkich-type khachkar with the crucified Christ and Bible scenes. In Yerevan, you can still watch carvers at work today.

Significant Khachkars Outside Armenia

Khachkars stand far beyond Armenia too. Many modern pieces honor the victims of the Armenian Genocide and serve as signs of memory and strength for the diaspora. You can find them at the Vatican Museums, Canterbury Cathedral’s memorial garden, St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney, the Colorado State Capitol, the Temple of Peace in Cardiff, and Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin. France alone has nearly 30 public khachkars, and Poland has around 20, reflecting long-standing Armenian communities.

Historically, many khachkars stood in areas of historic Armenia now in Turkey, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Iran. Many there were destroyed. The worst case is the loss of about 10,000 khachkars at the Julfa cemetery in Nakhichevan between 1998 and 2005. Still, surviving stones outside Armenia show the broad reach and importance of the art.

Museums and Outdoor Collections

Museums worldwide display khachkars so more people can see them. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York shows a 12th-century “Khachkar (Stone Cross)” from Lori-Berd made of basalt (about 2000 lbs/907.2 kg), featured in the 2018-2019 “Armenia!” show and now in Gallery 300. The British Museum holds a khachkar from Noraduz, given in 1977 by Catholicos Vazgen I.

For its March 2023 show “Breath of God”: Armenia and the Bible, the Museum of the Bible received two large, finely carved khachkars as gifts-replicas of the Noravank and Tatev Monastery stones by modern master Ruben Nalbandyan. Such displays help protect and share the art with a wide audience.

UNESCO World Heritage Sites Featuring Khachkars

UNESCO added khachkars and their craft to the Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2010. Several World Heritage Sites in Armenia also feature them, especially the monasteries of Haghpat and Sanahin in Lori Province. These complexes show the stones in their original settings-part of church buildings and grounds.

Seeing khachkars at these sites helps visitors grasp their role in Armenian Christian architecture and landscapes. Their presence at World Heritage Sites supports protection and public understanding of this cultural treasure.

Conservation and Threats to Khachkar Heritage

Khachkars are beautiful and spiritually rich, but they face many risks. Many have lasted for centuries thanks to strong stone and careful carving, yet they are still exposed to time, weather, and human harm. Protecting them takes steady work so future generations can know them.

Understanding these threats-from erosion to deliberate damage-shows why protection efforts matter and how fragile this art can be.

Natural Erosion and Environmental Damage

Weather wears down stone over long periods. Wind, rain, frost, and quakes all take a toll. Fine lacework is especially at risk as details fade with time. Climate shifts and pollution can speed up the damage, softening edges and weakening the stone.

Even in Armenia, some khachkars suffer from exposure and neglect. Tuff offers beauty and workable texture, but it can decay over time, so regular checks and protective steps are needed to keep details from disappearing.

Vandalism, Destruction, and Endangered Khachkars

Human actions have caused the worst losses, especially in disputed regions. The most tragic case is the Armenian cemetery at Julfa in Nakhichevan (Azerbaijan). Once home to about 10,000 khachkars in 1648, it was destroyed between 1998 and 2005, despite a 2000 UNESCO order for protection. Thousands of irreplaceable stones were wiped out. In Turkey, many khachkars have also been removed since the Armenian Genocide period, making tracking hard where records and photos do not exist.

Inside Armenia, damage can also come from neglect, moving stones for decoration or new holy sites, or clearing space for burials. These acts can strip khachkars of their historical setting and harm their integrity.

Efforts in Preservation and Restoration

Many people are working to save khachkars. The 2010 UNESCO listing was a key step that raised global awareness and support for protection.

In Armenia, projects document, restore, and protect stones. Museums like the Historical Museum in Yerevan and the collection near the cathedral in Echmiadzin play an important role by housing and caring for key examples. Specialists repair damaged stones and help slow further decay. Modern masters like Ruben Nalbandyan also make accurate replicas, passing on methods and designs so the craft does not fade. These local and international efforts help keep khachkars safe and known.

Modern Trends and Revival of Khachkar Art

Though ancient, khachkar art is very much alive. The 20th and 21st centuries brought a strong revival. Artists work within tradition while also adapting forms for today. This shows how powerful khachkars remain as signs of Armenian identity and as a living art.

Current work is not just about keeping the past; it also reinterprets it and pushes design forward, while keeping the core meaning clear. This balance keeps the craft growing.

Contemporary Artists and Innovations

The 20th century saw a major comeback for khachkar carving, and the momentum continues today. Many new stones are made in Armenia, honoring classic layouts or recreating historic designs to keep forms and skills alive.

Other artists explore new ideas within the basic “rules”-a central, framed cross-while adding fresh elements. In Yerevan, master Hambik Hambardzumyan works this way: he sketches, revises, and blends classical patterns with new thoughts. He says, “if one wants a khachkar to be beautiful, there must be freedom in its design and freedom in the amount of time it takes to create it.” This mix of tradition and creativity keeps the art current.

Role of Khachkars in Armenian Identity Today

Khachkars still stand as strong symbols of Armenian identity. They link people to Christian faith, honor ancestors, and show the resilience of the nation. In a fast-changing world, they offer a solid link to ancient roots. Their layered surfaces invite people to look closely and find meaning in culture and belief.

Because khachkars appear across Armenia-at churches, monasteries, cemeteries, and city streets-they remain part of daily life. They recall past struggles and hopes and point to the country’s spiritual base. Carving khachkars has become a cultural touchstone that builds shared memory and pride.

Khachkar Art in the Armenian Diaspora

For Armenians abroad, khachkars carry special weight. Hundreds serve as memorials worldwide, many honoring victims of the Armenian Genocide. Found from the Vatican Museums to parks in France and Poland, they mark remembrance, healing, and endurance.

In diaspora communities, khachkars are not just art; they are anchors of identity that connect people to their homeland. They support shared memory and show Armenian presence in many countries. Social media and global networks help new work reach communities abroad, who can commission and receive stones, keeping the tradition active across continents.

Frequently Asked Questions about Armenian Khachkars

How Are Khachkars Different from Tombstones?

Many khachkars stand in cemeteries, but they differ from typical tombstones in key ways:

- Wider purpose: they pray for the souls of the living and the dead, mark victories, church construction, or ask protection from disasters. Their role is often communal and spiritual, not only personal.

- Art and meaning: they carry deep, complex designs-crosses, rosettes, interlace, and plant motifs-with rich theology and culture behind them. Deep, layered carving invites reflection on faith and eternity, beyond simple name-and-date inscriptions.

Armenian grave markers come in many forms, but only a share are khachkars. This sets them apart as a special art.

What Makes Armenian Khachkars Unique in World Art?

Khachkars are unique because the central cross is paired with rich plant and interlace designs instead of a plain cross. This blend of Christian symbol and Armenian decoration is rare elsewhere.

Endless lines and geometric layers, carved at different depths, create a visible sense of continuity and mystery and point to the cross at the center. Amenaprkich-type stones add a figure of Christ on the cross, bringing a distinct icon style. Rooted in a line from the 9th century to today, and praised by UNESCO for meaning and craft, khachkars form a unique Armenian gift to world art.

Can Visitors See Active Khachkar Workshops?

Yes. In Yerevan, for example, a khachkar studio on Aram Street has no doors, so people can watch artisans at work. It offers a clear view of how these stones are made today.

Masters like Hambik Hambardzumyan, whose workshop is at Arami 29 Street, often share knowledge with visitors. Some studios offer classes where you can try carving tuff yourself. These visits give a direct link to a living tradition and show how much dedication the craft requires.

Leave a comment