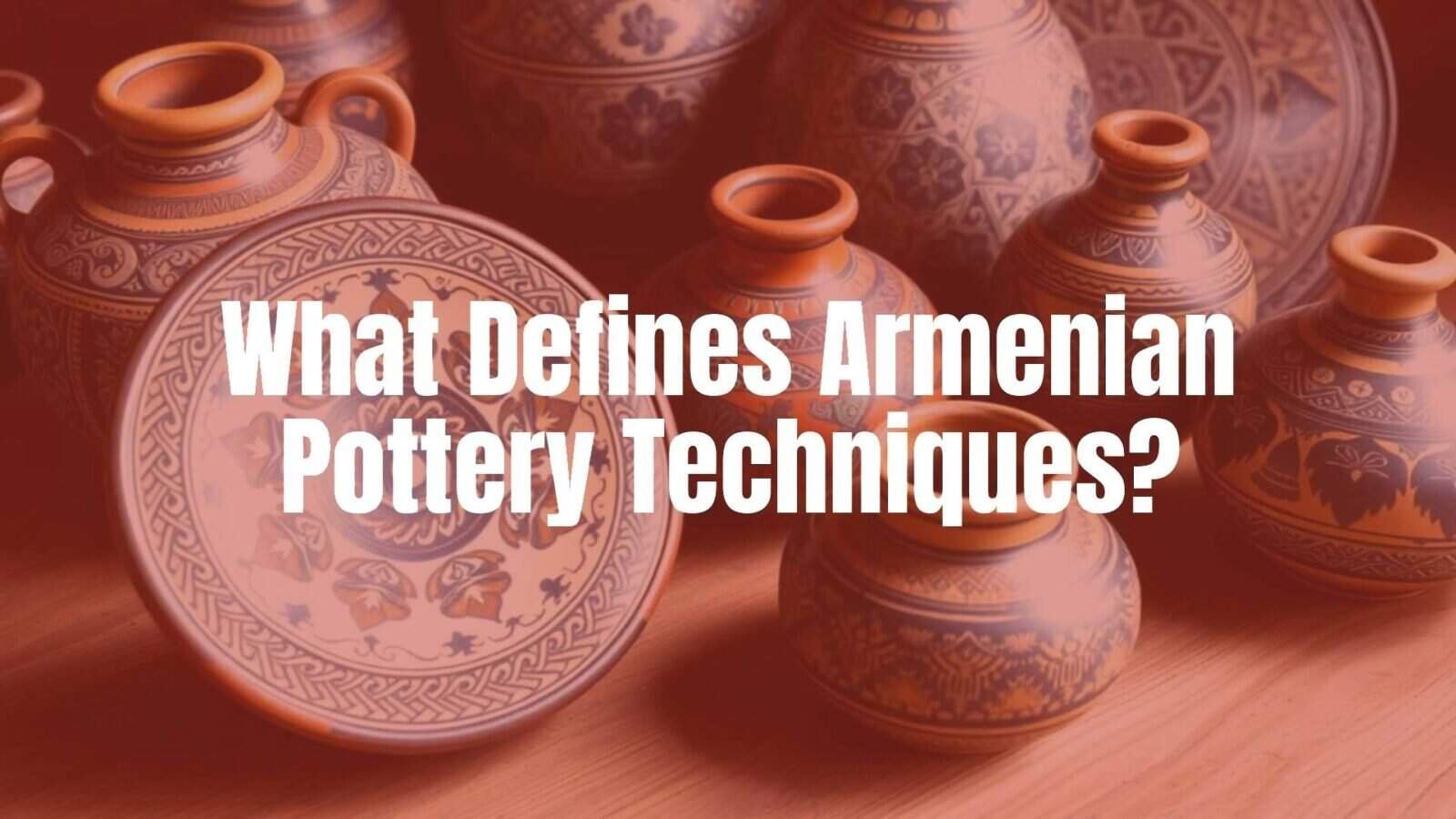

Armenian pottery techniques grow from centuries of practice, local materials, and steady artistic change. Makers rely on the land, using rich clay deposits found across the Armenian highlands. This long tradition turns simple earth into useful and beautiful objects that carry stories and symbols from Armenian culture going back thousands of years.

Armenian pottery stands out for its warm colors, detailed patterns, and meaningful designs. Nature, faith, and history often inspire these elements, giving each piece a clear character. From early hand-formed items in the 6th millennium BC to later glazed works, Armenian pottery blends daily use with art, showing a steady rise in skill and imagination.

Key materials and clays used in Armenian pottery

Armenian pottery depends on plentiful local clays. The highlands hold many deposits that have supplied potters for ages and helped shape the craft’s unique look.

Red clay was widely used for its strength and deep color, often dug from places like Dvin, the medieval capital, and the Ararat Valley. Black clay came from areas such as Aparan, Shirak, and Syunik. Each clay type adds its own qualities to the final piece.

| Clay type | Main sources | Key traits |

|---|---|---|

| Red clay | Dvin, Ararat Valley | Strong body, rich red tone |

| Black clay | Aparan, Shirak, Syunik | Distinct color, smooth finish |

Core processes in shaping and firing

The path from raw clay to a finished pot has several careful steps. Early pieces from the 6th millennium BC were hand-shaped. By the mid-2nd millennium BC, the potter’s wheel changed the craft, making more complex forms possible.

After shaping by hand or on the wheel, pieces dry for days before firing. The first firing (bisque) is about 1,000°C for around 24 hours. It hardens the clay and prepares it for glaze. The second firing, usually 1,200-1,250°C for about 24 hours, vitrifies the body and fixes the glaze. This two-step firing gives Armenian ceramics their strength and look.

| Stage | Temperature | Duration | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisque firing | ~1,000°C | ~24 hours | Clay hardens; ready for glaze |

| Glaze firing | 1,200-1,250°C | ~24 hours | Body vitrifies; glaze bonds and shines |

Historic motifs, glazes, and decorative patterns

Decorations in Armenian pottery connect closely to history, faith, and nature. Early vessels often show animals, trees, and symbols. After Armenia adopted Christianity in the 4th century, crosses, saints, and scenes from the Bible appeared on tiles and pots, especially for church use.

Glazing grew over time, adding color and protection. Medieval centers like Dvin and Ani used deep cobalt blue and greens. Potters in Dvin also made “transparent” faience by piercing tiny holes in the clay before adding a clear glaze, creating a soft, see-through effect like fine porcelain. Later, in Kutahya, Armenian makers produced striking tiles and wares with turquoise, green, and the well-known “Armenian bole” red, a shade linked with Iznik pieces. These choices in color and motif help tell the ongoing story of Armenian art.

How have Armenian pottery techniques evolved through history?

Armenian pottery has changed across thousands of years, adjusting to new tools, shifting times, and outside ideas. The craft moved from simple, useful items to highly refined works, showing steady skill and dedication to making things well.

By keeping function and art together, Armenian ceramics survived hard periods and outside rule. Each era added forms, styles, and methods, creating the wide range seen today.

Ancient and medieval origins

Armenian pottery began in the 6th millennium BC during the early pottery Neolithic. First pieces were plain but set the base for later growth. By the 3rd millennium BC, colored ceramics appeared. The Bronze Age brought black-burnished pottery, showing early style and technique.

The potter’s wheel became common by the mid-2nd millennium BC, greatly improving production and shape control. In the Kingdom of Van, pottery reached new levels. In medieval times, Dvin and Ani were busy centers. Craftsmen formed guilds called amkars, which supported shared learning and advanced glazing with colors like cobalt blue and green. Dvin led faience work from the 9th to 13th centuries.

Influence of religion and geography

Armenia’s landscape, with its fine clay deposits, shaped how pottery looked and felt. Red clay from Dvin and the Ararat Valley and black clay from Aparan, Shirak, and Syunik provided the main raw materials. Using these local clays helped build a distinct regional style.

Faith also guided design. After the 4th-century adoption of Christianity, signs of belief-saints, crosses, and Bible scenes-filled many works, especially for churches. Earlier nature themes like animals and the sun also remained common. Together, land and faith formed a pottery tradition closely tied to Armenian identity.

Adaptations during Ottoman and Persian periods

Changing empires left a mark on the craft. As Iznik’s influence faded under the Ottomans, Armenian potters in Kutahya grew in importance from the 15th to 18th centuries, turning the city into a major center. They made tiles and fine tableware, with some exports to Europe.

Islamic rules sometimes limited images of living beings. Armenian artists responded with strong floral and geometric designs, showing skill within those limits. Kutahya wares often served homes and repairs, used simpler patterns, and included Armenian writing. Despite pressure, artisans kept their voice and carried on their work.

Revival and innovation in the 20th century

The 20th century brought hardship and fresh growth. After the 1915 Armenian Genocide, many potters from Kutahya settled elsewhere, including Jerusalem, where new workshops opened. This movement mixed older styles with new ideas, giving rise to well-known motifs like “dancing animals” and “moving trees.”

In Armenia, pottery continued and later saw fresh energy. The late 20th and early 21st centuries brought projects to document and renew traditional methods. Groups like Sisian Ceramics (founded by Vahagn Hambardzumyan and Zara Gasparyan in 2004) revived ancient ways while adding modern touches. Artists such as Mane Brutents blend minimal forms with Armenian poetry, keeping the craft active and connected to both past and present.

Which tools and methods are central to Armenian pottery?

Armenian pottery uses long-tested tools and methods passed down through families and workshops. These steps turn raw clay into useful and decorative pieces. Shaping, drying, glazing, and firing each play a key role in the final result.

The look and feel of Armenian ceramics come from this mix of practical skill and artistic choice. Makers can repeat classic forms or create new ones by building on these basics.

Hand-building versus wheel-throwing techniques

Two main shaping methods are common: hand-building and wheel-throwing. Hand-building uses the maker’s hands and simple tools to form clay without a wheel. It suits unique, irregular, or larger shapes and includes coiling, pinching, and slab work.

The wheel, widely used since the mid-2nd millennium BC, allows quick, even forms like bowls, jars, and other vessels. Master potters such as Vazgen Gevorgyan teach both basic throwing and more advanced shaping. Many artists, including Mane Brutents, mix wheel-work, hand-building, and liquid clay techniques to reach different artistic goals.

Distinctive glazing and firing methods

Glazes add color, shine, and a waterproof surface after the first firing. Historic palettes include cobalt blue, green, turquoise, and the deep “Armenian bole” red linked with Iznik.

Armenian potters also developed “transparent” faience, especially in Dvin. They pricked tiny holes in the clay before adding a clear glaze, making a soft, translucent effect. Firing follows two stages: a first firing around 1,000°C to harden the body, then a higher firing at 1,200-1,250°C to melt the glaze and give strength and luster. Traditional tonir hearths served for firing in the past, alongside today’s modern kilns.

Common tools in traditional workshops

Workshops rely on simple, effective tools:

- Potter’s wheel for round, even forms

- Wooden and metal ribs for smoothing

- Cutting wire for portioning clay

- Modeling tools for sculpting details

- Sponges for cleaning and moisture control

- Brushes for glaze and hand-painting

- Incising tools for carving patterns

- Kilns (tonir, gas, or electric) for firing

What are the most recognized styles of Armenian pottery?

Armenian pottery includes several styles linked to place and time. Each has its own look, shaped by trade, faith, and local taste-from a historic market city to a community rebuilt in a new land.

Knowing these styles helps you see how tradition stays alive while artists keep adding new ideas.

Kutahya style: features and legacy

Kutahya in western Turkey became a key center from the 15th to 18th centuries, peaking between the 17th and 19th. Armenian makers produced tiles for churches and household wares, sending some pieces to Europe. Designs often show flowers, religious scenes, and Armenian writing, usually with clear, simple layouts.

Early Kutahya items often used white and blue; later works added red and full-color patterns. These pieces favor clean motifs and practical beauty. The Armenian Cathedral of St. James in Jerusalem features Kutahya tiles with colorful Bible scenes. The Kutahya industry ended after Armenians were forced out during World War I, but its impact shaped later work, especially in Jerusalem.

Jerusalem Armenian ceramics

Jerusalem Armenian ceramics began in 1919, started by Armenian potters from Kutahya who survived the Genocide. Makers like David Ohannessian and Neshan Balian, Sr. opened workshops in the Armenian Quarter, which soon became a busy center.

Jerusalem wares blend Kutahya roots with new energy: lively “dancing animals,” “moving trees,” and fine floral and geometric patterns. Tiles and plates decorate churches and homes across the city. Family studios such as the Balians and Karakashians continue today, keeping the tradition active while mixing classic and modern art.

Modern interpretations and diaspora influences

Contemporary artists carry the craft forward with new forms and ideas. Many combine classic shapes and glazes with abstract or sculptural styles, offering fresh looks that still feel Armenian.

For example, Mane Brutents builds a brand around clean design, Armenian poetry, and the familiar white-and-blue palette tied to Kütahya masters. Armenian studios in the US, Canada, Australia, and Europe keep the craft present worldwide, blending heritage with wider influences so the art stays current and alive.

What distinguishes authentic Armenian pottery?

Authentic Armenian pottery brings together age-old methods, recognizable design choices, and the maker’s hand. Each piece carries craft traditions, symbols, and clear links to place and workshop.

Genuine works connect to many generations of artists and to Armenian identity. Knowing what to look for helps buyers and fans value these pieces.

Signatures of craftsmanship and common marks

Real Armenian pottery often shows marks that point to its maker or studio. These can be stylistic traits, Armenian inscriptions, or family signatures. In Jerusalem, the Balian and Karakashian workshops are well known, and their pieces often carry marks that identify them.

The handmade nature is also a sign. True pieces show fine handwork and small variations that reflect the person who made them. This careful attention-from shaping to glazing and painting-sets them apart from factory-made copies, which often look uniform and lack depth in detail.

Traditions in shaping and hand painting

Shaping on the wheel and hand-building both signal real craft. These methods, refined over centuries, give balanced forms that work well and look pleasing.

Hand-painting is another strong marker. Many pieces carry floral and geometric patterns, animals, or faith-based images. Colors like cobalt blue, turquoise, green, and “Armenian red” often appear under clear glazes that make them glow. Hand-painted work, rather than decals, points to authenticity and respect for tradition.

Tips on evaluating and caring for Armenian ceramics

When you look at a piece, check for:

- Armenian inscriptions or family marks (e.g., Balian, Karakashian)

- Fine, varied handwork rather than uniform factory finish

- Color sets linked to Armenian styles: bright blues, greens, and reds

Care guidelines:

- Avoid soaking, especially with older or unglazed items

- Wipe with a soft, damp cloth; skip harsh cleaners and abrasives

- Keep away from sudden temperature changes, direct sun, and high moisture

- Use display cases for delicate or rare pieces

- Pack with soft materials like bubble wrap when moving

- Use a professional restorer for any repair work

Where can you see and experience Armenian pottery techniques today?

You can meet this living craft in Armenia and across the diaspora. It is active in studios, classes, and family workshops, not just museums. Visitors can watch, learn, and take part.

Whether you collect, travel, or want to learn, many paths lead to Armenian ceramics and its makers.

Key pottery centers in Armenia and the diaspora

In Armenia, Gyumri is known for arts and crafts. Gevorgyan Ceramics, founded by Vazgen and Satenik Gevorgyan in 2008, works to renew pottery traditions of the highlands, using local clay. Sisian Ceramics, started in 2004 by Vahagn Hambardzumyan and Zara Gasparyan, draws on ancient sites like the Ukhtasar Petroglyphs.

Outside Armenia, the Armenian Quarter in Jerusalem remains a strong center. The Balian and Karakashian studios, founded by refugees from Kutahya in 1919, still blend classic styles with new art. Armenian potters across the US, Canada, Australia, and Europe also keep the craft visible worldwide.

Workshops and masterclasses: learning with artisans

Hands-on learning brings the craft to life. In Gyumri, Gevorgyan Ceramics offers lessons with Vazgen Gevorgyan, from basic wheel-throwing to more complex forms, mixing traditional clay prep with modern ideas for a well-rounded experience.

Sisian Ceramics in the south runs small masterclasses with Vahagn Hambardzumyan and Zara Gasparyan. Guests can throw a clay mug on the wheel and take home what they make. Along the way, makers share the history behind the methods.

Significance of pottery festivals and cultural events

Festivals and cultural shows help share, protect, and grow Armenian pottery. They give artists space to display work, teach methods, and meet collectors and fans.

Large events may vary, but Armenian ceramics often appear at museum shows and art fairs around the world. Local and international exhibitions support handmade art and help keep Armenian pottery active and inventive.

Frequently asked questions about Armenian pottery techniques

Why are specific nature and religious motifs prevalent?

Armenia’s long Christian history shaped its crafts, so crosses, saints, and Bible stories often appear, especially on church pieces. The bond with nature also runs deep: early works show animals, the sun, and plants. When rules limited human and animal images, artists turned to floral and geometric designs. Later, especially in Jerusalem, makers freely added lively animals like peacocks (long life) and gazelles, along with flowing trees. These images reflect faith and the land.

How are Armenian pottery techniques used in everyday life today?

While large wine jars (karas) and clay ovens (tonir) are now mostly historical, Armenian ceramics still serve daily needs. Bowls, mugs, plates, and serving dishes bring cultural touch to the table. Makers like Mane Brutents produce custom tableware for restaurants, linking tradition with today’s kitchens.

Beyond the home, ceramics are popular souvenirs in Armenia and Jerusalem. Many pieces are collected as art, and some appear in buildings and public spaces. Artists also try new forms, including clay jewelry, keeping the craft fresh and useful.

What sets Kutahya, Jerusalem, and other regional techniques apart?

Kutahya, active from the 17th to 19th centuries, used clear, simple styles for home goods and church tiles. Floral or religious themes and Armenian writing often appear. Early works focused on white and blue; later ones added red and full-color patterns.

Jerusalem, founded by Kutahya-trained refugees in 1919, widened the range with lively “dancing animals,” “moving trees,” and rich patterning. Family studios in the Armenian Quarter still produce these pieces. In Armenia, studios like Gevorgyan Ceramics and Sisian Ceramics revive highland methods, use local clays, and blend traditional approaches with new design. Each place offers a distinct path into Armenian ceramic art.

Leave a comment